Data Burdens

Hi friends,

Friday morning, as I got to engage in a wide-ranging discussion about what firms and policymakers can do to address the inequalities that undermine growth, the conversation kept coming back to a core question: what will it take to power the economy without pushing the costs onto working families? There’s a finite supply of electricity, and a growing share of power demand itself is coming from the data centers powering artificial intelligence, cloud computing, and digital services we use daily. This is driving up prices, as rising demand meeting not-rising-fast-enough supply tends to do. The race to scale artificial intelligence is outpacing consideration of who wins the demand competition, and the result is an economy powered by pushing higher costs onto working families.

Read on—just one chart and 758 words.

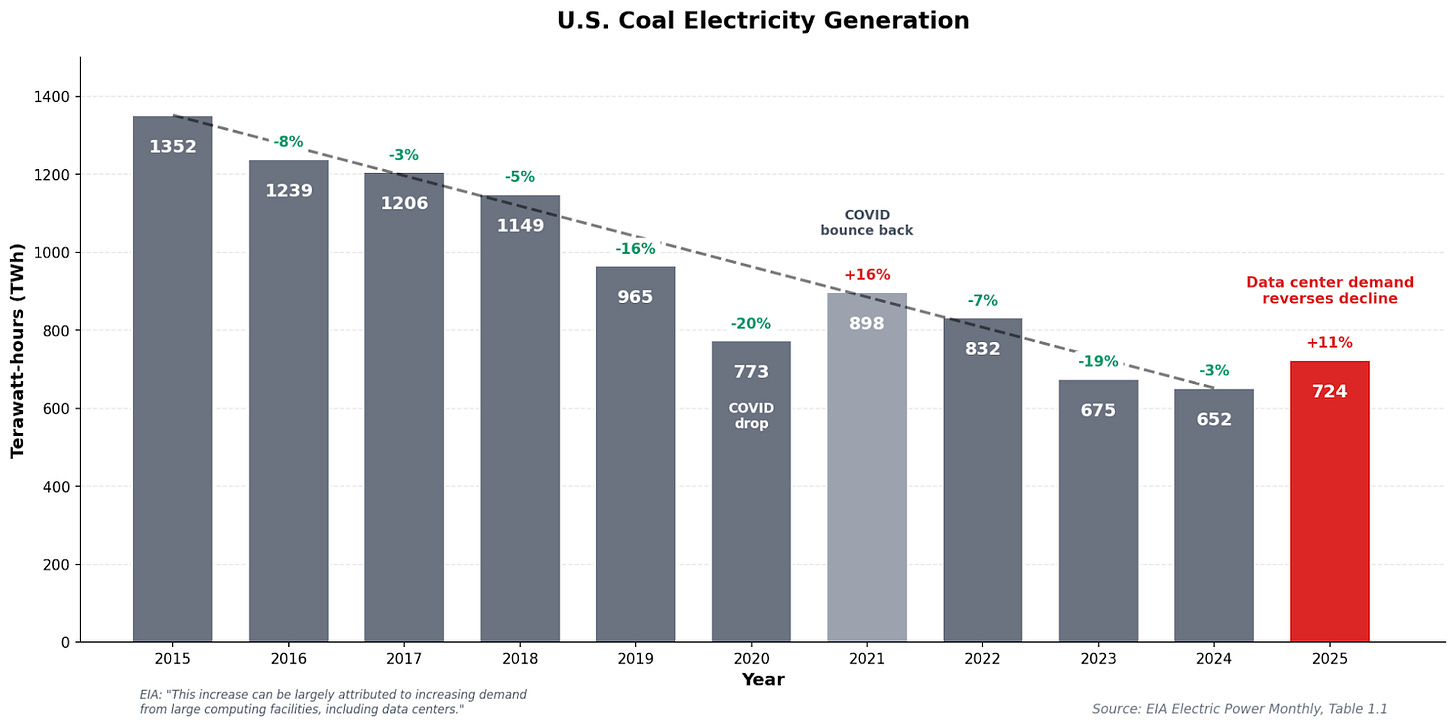

Chart of the Week: Since 2015, levels of coal electricity generation have fallen. However, as data centers and households compete for grid space, the trend is reversing. Relative to 2024 levels, coal electricity generation increased 11% in 2025.

Power surge: Overall inflation held steady in December at 2.7%, above the Fed’s 2% target but obscuring the fact that electricity prices are up 7% year over year. In the rush to meet increased demand, utilities are keeping coal plants they previously planned to close online, while households and big tech companies are left to compete for limited grid space.

The basics: Data centers are massive warehouses filled with computer servers that need constant cooling. A single data center can consume as much power as 100,000 homes.

The basic responsibility of grid operators is to meet demand with sufficient supply, and they’re highly regulated and face oversight to ensure they meet the nation’s energy needs. The spike in demand from data centers—at a faster rate than can be either forecasted or built around—has left many utilities and generators with few options but to keep aging and expensive-to-operate coal plants running.

Quick fact: Amazon Web Services, Microsoft, and Google account for nearly 60% of all hyperscale data center capacity, over half of which is based in the United States.

As a result of the run-up in demand, over 25 gigawatts of coal plants scheduled for retirement will remain online. Costs of delayed retirements are passed to all ratepayers, not just the data centers driving demand.

Case in point #1: A coal plant in Wisconsin that emits more greenhouse gasses than one million cars annually was set to close in 2024 but is now scheduled to run until 2029.

… #2: The last of Maryland’s large-scale coal plants was originally slated to close in 2025. Now, under a “reliability must-run” agreement—which keeps plants running while grid upgrades are built—the plant will run until 2029.

Keeping the plant operating for the next four years could cost ratepayers $180 million annually, adding roughly $60 per year to the typical Baltimore-area electricity bill.

A bad deal: Operators began retiring coal plants decades ago because these facilities were outdated and more costly to run than power plants relying on renewables. Additionally, the Inflation Reduction Act tax credits meant that 99% of all U.S. coal plants were more expensive to run than power plants running on renewables.

To put it in context: PJM interconnection serves 65 million people across 13 states—Ohio, Indiana, Kentucky, as well as some northeastern states. This year, data centers accounted for 63% of all increased demand for PJM, causing capacity market prices to jump nearly tenfold and contributing to $9.3 billion in rate increases.

In Washington, D.C.—one of the areas served—households saw prices rise by $21 per month, with roughly half attributable to data center demand.

Oftentimes, working families ultimately subsidize data centers three times over: through tax breaks, ratepayer-funded grid upgrades, and a slower transition to clean energy (power sector emissions could increase 30% compared to a scenario without data center growth).

Statewide demand struggle

Indiana: In 2019, to incentivize projects and grow the state’s economy, the state legislature passed a data center tax exemption, meaning companies that invest in building new data centers avoid the state’s 7% tax on equipment and power purchases. As of June, Indiana was processing 30 data center proposals.

Ohio: In July, average electricity bills in Columbus were over $50 higher compared to a decade ago. Statewide, the PJM capacity auction resulted in pricing 833% higher than the prior year, driven largely by data center demand. The increase in auction pricing is estimated to lead to a rise in electricity bills for residential customers by up to 15% and for businesses up to 29%.

Virginia: Data centers account for over a quarter of some utilities’ total electric demand in Virginia, now home to the world’s largest concentration of data centers. In Central and Northern Virginia, by 2030, electricity costs could rise more than 25%—the highest regional increase in their model. Currently, Virginia utilities import 40% of their own power supply from elsewhere, the highest rate of any U.S. state.

The economy is built on business development and technological innovation—both of which need power. There is an opportunity to scale renewable power; failing to do so leaves families and communities footing the bill for outdated infrastructure and in a “pay-to-play” system that inherently favors Big Tech. As many states are beginning to see, the costs are socialized. The benefits are not.

Best,

Heather

“As many states are beginning to see, the costs are socialized. The benefits are not.”

I hope they see this in more situations than just electric generation. Taxpayers subsidize businesses in many ways.

If data centers had solar arrays covering their very large roofs, would it significantly reduce their demand on their grid? If so, requiring them to build their own power source would push much of the cost of their demand onto them.